HistoryThe Post- Meroitic EraThe golden age of Kush has arguably ended around 350 CE. Grand projects and large-size pyramid and temple construction were rarely carried following the former date.1 Archeological evidence suggests that after the fourth century CE, the kingdom of Kush had experienced extensive nomadic invasions from the surrounding deserts.

These, often hostile, desert nomads seem to have competed with the Kushites for control over territories and resources. They also contributed to the unstable situations in the southern territories of Roman Egypt. The kingdom of Kush, nevertheless, continued to hold itself until the mid-fourth, or even fifth, century.2 A poweful group among these nomads were the Nobatians— or perhaps the Nubians.3 Starting from the third century, they began to occupy and settle the Nile Valley. In process, they fought with the Kushite kingdom and probably fascilitated its eventual shrinkage. Meroitic inscriptions found at the temple of Kalabsha, though mostly undeciphered, provide some important indications on the historical circumstances of the period. A three word phrase in the inscriptions was deciphered as referring to a certain king "Kharamazeye".4 Translation of some phrases reveal a prayer that calls for Kharamazeye to be crowned as the "monarch [and] commander of Great Napata.".5 Kharamazeye was probably a Nubian king. In the mid-fourth centurey, Kush has endured small-scale invasions from the kingdom of Axum (in what is today Ethiopia) to the southeast of Sudan.6 An Axumite inscription, in the same century, narrates a campaign carried by the Axumite king Ezana in eastern Sudan against desert tribes called the Blemmyes, also known as the Medjay. The inscription claims that the Blemmyes have rebelled against Axumite rule.7 More important are the list of enemies Ezana claims to have confronted which included the "Kasu [Kushites]" and the "Noba [Nubians]".8

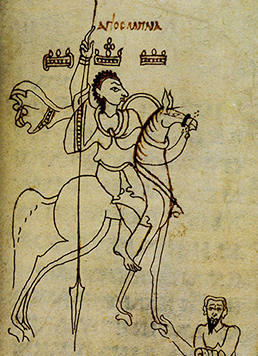

The fifth century CE inscription of Silko, "King of the Noubades [Nubians] and all the Aithiopians [Kushites]",9 written in Greek, together with other deciphered inscriptions, indicate some sort of continuity with regards to the native society of the people of Kush. The last known Kushite king to be buried under a pyramid was Pharaoh Yesbokheamani (although Teqerideamani is the last Kushite king for whom there is absolute chronology), who lived in the third century.10 Starting from the first century CE, the scale of Meroitic pyramids began to gradually reduce in size. The latest pyramid is dated to around the mid-fourth century.11 The Nubians did not build pyramids for their desceised but followed the tradition of tumulus burials. Tumuli are found throughout North Sudan, particularly at Sururab el-Hobagi south of Khartoum.12 The owners of the late tumuli structures are thought to have been Nubian rulers. This change of funerary architecture represents the upstart of cultural changes that drastically transformed the future society of Sudan.

Edited: Jan. 2009. |