Daily LifeAgriculture and Diet

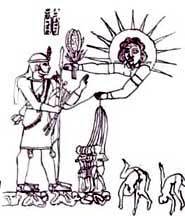

Agriculture along the narrow strip of the Nile Valley provided the people of Kush with their necessary food supply. Each year the Nile flooded providing silt for the fertile agricultural lands of Sudan. The Kushites used the Shaduf, i.e. a traditional device operated manually for raising water from a lower depression to a higher depression where the water is distributed through other depressions to irrigate the fields.1 Sometime in the late Meroitic period, the Kushite farmers began to use the Saquia, i.e. a water wheel brought to Sudan from southwest Asia.2 Numerous hafirs, i.e. depressions dug on flat grounds to collect rain water, were discovered in Sudan, including in Musawwarat es Sufra.3 However hafirs would not have always provided enough water for the farms. The only known Kushite dam used for water storage was found at Shaq el Ahmar.4 Nomads wandered the semi-arid regions on both sides of the Nile Valley with their flocks in search of good pastures. In some senarios, the nomads and the farmers of Kush have benefited from each other, i.e. exchanging animal products for agricultural produce and the vise versa. The farmers of Kush allowed the nomads to herd their flocks on harvested farms so that the dung of the animals would fertilized the farms.5

Barely, sorghum, and wheat were probably the most commonly cultivated crops in Sudan.6 Accordingly, bread was perhaps the most widely produced food as best attested in the bakeries and ovens of Kerma.7 The making of bread, using wheat and barley, is best represented in the archeological remains of ovens in Kerma. Barley was particularly found stored in silos.8 Sorghum, on the other hand, was easily grown in Sudan's Buttana region. In fact, one of the primary reasons behind the expansion of the Kushite kingdom in the Butana region, during the Meroitic period, was probably the cultivation sorghum. Some excavations uncovered evidence for broomcorn millets, and melon seeds.9 Evidence for cucurbits, and legumes were found,10 as well as peas and lentils in the Wadi Halfa area.11 A realistic description was provided by the Roman Geographer Strabo in the second century CE:

Date is a sweet fruit that grows in palm trees. Dates are one of the most available fruits along Sudan's Nile Valley and were used to make wine, as well as a variety of desserts just as the case in traditional Sudanese culture today.13 Lalop is another type of fruit that was probably eaten in Kush. This fruit is distinguished by a thin layer of sweet and edible fibers that wrap an inner seed. The extensive production of a different palm fruit called doam is evident from New kingdom Egyptian relieves in which Kushites are depicted as carrying gifts to the Egyptian pharaohs. Other fruits may have included oranges, tamarind, and grape-fruits, all of which are widely grown in Sudan today. One non-dietary crop that is widely grown in Sudan today, and was grown in ancient times, is cotton. Used domestically for cloth making, and possibly transported to other locations, cotton clothes were abundantly found in Kushite graves, including the cemeteries at Kerma.

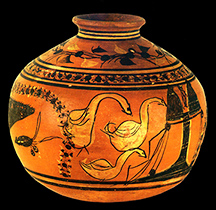

Animal food products: Other than agricultural products, the Kushites ate a variety of animal products. In the first century, a Roman geographer wrote that the Kushites, "use meats, blood, milk, and cheese"(Strabo xvii Ch. 2: 2) for food. Cheese was popularly manufactured as evidenced from funirary findings. Unlike the Egyptians, the Kushites extensively domesticate cattle and sheep. Extensive leftovers of sheep bones were found on offering chapels and temple kitchens in Kerma.14 Cattle were also sacrificed in great numbers in the Kerma graves indicating their religious importance in the Kushite life. Evidence of antelopes were also found in conjuncture with hunting activities;15 thus, it is likely that they were also a source of diet. Pigs may have also been domesticated for food in limited numbers, though—like in Egyptian and other Near Eastern cultures—pork may have been a forbidden food in Kushite culture. Fish was a popular and an inexpensive food in the ancient Sudan. Residues of fish were found in different sites.16 Fishing in Sudan is an activity that dates way bak to prehistory, perhaps predating the development of agriculture and animal husbandry. One of the major advantages of the Nile River to the early inhabitants of Sudan, was its fish. Evidence from Kerma dating to the fifth or sixth century BC indicates that the Kushites did eat fish, particularily fish sauce.17 Today in Sudan, fish is traditionally dried, salted, and then boiled with water to make a type of sauce known as fasikh'. Birds—ducks, geese, and chickens18—were also domesticated. Although cattle and sheeps/goats were more popular as diet than birds. Ostrich egg shells were extensively used in a variety of industries, which supports the idea that the yokes were eaten. In the ancient cemeteries of Kerma, ostrich eggs were highly common. In Sudanese folklore today, ostrich eggs are commonly cited as food. Finally, this particular offering table from Meroe provides a great visual demonstration for the food variety in the ancient kingdom of Kush. The tablet depicts grapes, meat slices (probably of cattle), prepared geese, and bread rolls.

Edited: Marc. 2009. |